Gnostics believed that the sensible world is the creation not of God but of a flawed subordinate divinity, the Demiurge, whose ignorance and self-centeredness affected the quality of his handiwork.

It’s a neat solution to the problem of evil. The maker of this imperfect world was kind of a dope, though he meant well. He just didn’t have all the necessary information to do the job right and was too full of himself to recognize his limitations.

The scientists in Luke Scott’s impressive directorial debut, Morgan, are demiurges, or demi-demiurges, who’ve spent five years raising and nurturing the title character, a being they created using a combination of human and artificial DNA. To say that Morgan is gifted is an understatement. She was, we’re told, able to walk and talk at one month of age and was self-sustaining at six months. She’s five years old when we meet her, but physically she’s a teenager. She also has nascent telepathic, telekinetic, and precognitive abilities. Morgan would appear to be a vast improvement on Homo sapiens, perhaps an evolutionary leap thousands of years forward. But, of course, there wouldn’t be a movie if she were merely perfect.

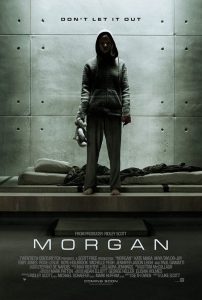

In the opening scene, on the black-and-white feed from an overhead security camera, we see Morgan, unsettlingly wraithlike in a gray hoodie, attack and partly blind one of the scientists working with her. The attack is unprovoked and, to the researchers, inexplicable. Morgan betrayed no violent tendencies prior to this incident. The company funding the project is understandably concerned and sends a risk-management expert, Lee Weathers, to determine whether the project should be shut down and Morgan terminated.

The idea is familiar enough. The genetic-experiment-gone-awry movie has a lengthy pedigree, and if I reveal that the problem with Morgan is that she was intended from the get-go to be a weapon, I’m giving away nothing that a seasoned moviegoer won’t guess from the setup. But Morgan stands out from the generic pack, for a few reasons.

Visually, Morgan is striking. Luke Scott is the son of Ridley Scott (who is an executive producer here) and has his father’s eye for light, but his sense of poetic composition is very much his own. An example. Morgan is kept in a cell in an underground laboratory. Only the entrance to this virtual bunker is visible, with a steel door set into a concrete structure surrounded by grass and flowers and trees. At first glance, it looks almost like one of Andy Goldsworthy’s rock sculptures in the middle of a meadow. The contrast between this manmade structure and the natural world around it is oddly beautiful and generates an effortlessly precise metaphor for the conflict between man and nature taking place below. Lest we relax into the old Romantic antagonism between man and nature, though, where man is bad and nature is good, Scott complicates the relationship by filming the pine forest around the remote location as ominously dark and threatening, like the forest of Germanic folklore, in which a traveler runs the risk, with every step, of getting lost forever.

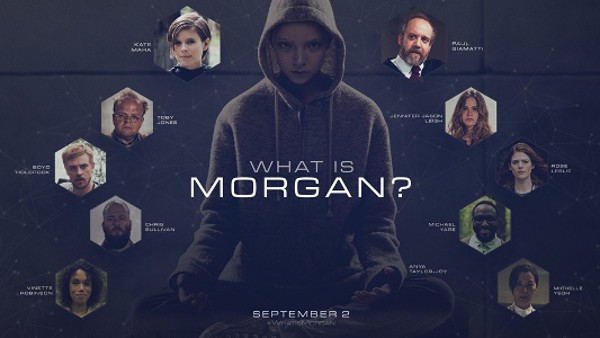

The acting is excellent. Jennifer Jason Leigh and Michelle Yeoh, because their characters are peripheral to the action, are mostly untapped resources. But Rose Leslie (“You know nothing, Jon Snow”) brings a nice touch of combative idealism to the free-spirited Dr. Amy Menser, and Toby Jones, as Dr. Simon Ziegler, registers a hundred gradations of anguish in his weary face as he comes to realize, against his heart, that the miracle he’s wrought may be irreparably flawed.

Kate Mara, in the lead, manages the difficult trick of making the icily professional Lee Weathers likable. Weathers is almost robotic in her fixity of purpose and lack of affect, but Mara uses the smallest gestures—an awkward smile, a slight widening of the eyes—to convey an inner life that the audience can connect with and hang on to, however tenuously.

But the real star is Anya Taylor-Joy as Morgan. The emotional content of the story depends on her performance. We probably wouldn’t believe in the researchers’ attachment to their creation if not for the fearful, childish ingenuousness that Taylor-Joy brings to the part. And when Morgan finally gives in to her impulses, embraces the fate written into her DNA, and becomes what she was always meant to be, the mixture of release and purposeful rage in her eyes is genuinely frightening.

(Speaking of frightening—the trailers and posters give the impression that Morgan is a horror movie. Science fiction thriller is more accurate. The audience will jump now and then but not from surprise. In almost every instance, we know all too well what’s about to happen. The fright is in the suddenness of the violence, which Scott cannily heightens by turning up the volume at the point of attack, so that when Morgan strikes, or when the gun goes off, we feel it viscerally, as a vibration in our guts. Morgan has one notably bloody moment but isn’t especially gory otherwise. Nonetheless, the violence is jarring. Sensitive souls beware.)

Luke Scott doesn’t appear to have inherited his father’s weakness for atmospheric longueurs. Morgan is a story told with great velocity. The setup is quick. Introductions to all the characters are made in a timely fashion. The wheels of the plot begin to turn immediately. Morgan feels even shorter than its ninetyish-minute running time. These days, when too many filmmakers seem to think they can offset substandard quality with oodles of quantity, an economy of narrative means is a reassuring sign that the director has confidence in his material. As Scott, in this case, certainly should.

That’s not to say Morgan is a perfect movie. The denouement, though superficially satisfying, raises a lot of questions the more you think about it. And given that Morgan can read minds, see the future, etc., it’s sort of a letdown to discover that her fully actualized self is essentially a waifish Jason Bourne. But these are quibbles. Morgan is a good flick and well worth seeing.

MORGAN OPENS IN THEATERS NATIONWIDE SEPTEMBER 2, 2016