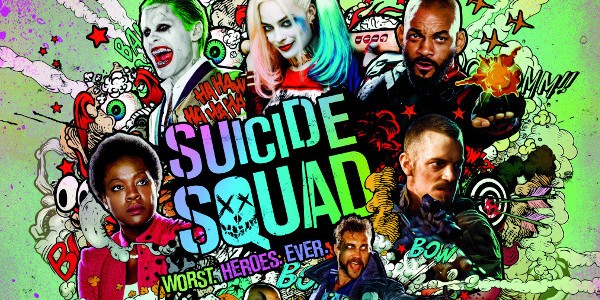

Superman is dead. That’s the first premise of Suicide Squad. Superman is dead, and Amanda Waller (played by Viola Davis), a ruthless U.S. intelligence officer, is worried that the next super-powered extraterrestrial being who falls to Earth won’t be as sympathetic to the American way as old Kal-El was. Her solution? Implant tiny bombs in the necks of half a dozen or so supervillains and press the poor bastards into service as needed, under threat of explosive decapitation.

Not that Waller’s plan isn’t eminently practical, but did it occur to her to ask Batman? If Ben Affleck’s cameos as the Caped Crusader in Suicide Squad are any indication, he’s available. So is the Flash.

Although admirably purpose-driven, Waller is morally challenged, to say the least. Later, she guns down several fellow—but, alas, lower-ranking—intelligence officers who were helping wipe all the hard drives in her office. “They weren’t cleared to see any of this anyway,” she says. (Q: Then why were they in her office in the first place? A: Look out! Another slew of ridiculous mutant minions to fight!) Apart from making gobs of money, this seems to be the point of Suicide Squad: to replace all the do-gooders of the superhero genre with do-badders forced by exigent circumstances to do right. It’s the triumph of utilitarianism over idealism. No categorical imperatives here. Just a bunch of superhumanly powerful psychopaths and murderers we’re supposed to judge on the basis of their acts. Now, they’re heroes.

So who are they? If you don’t know already, you should check out Fanboy Factor’s helpful primer here. In case you don’t feel like leaving this page, however:

Deadshot (Will Smith) is the world’s greatest hit man; his aim with a firearm is infallible.

Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie) is the Joker’s appropriately unhinged paramour.

El Diablo (Jay Hernandez) is a Latino gangbanger with pyrokinetic abilities.

Killer Croc (Adewale Akinnouye-Abaje) is aptly named.

Captain Boomerang (Jai Courtney) is an Aussie bank robber with an arsenal of tricked-out yo-yos. Just kidding. They’re tricked-out boomerangs.

And, finally, there’s Enchantress (Cara Delevingne), an ancient and vastly powerful “meta-human” that bygone civilizations worshiped as a goddess. When we first meet her, Enchantress looks like a Dickensian chimney sweep who’s been tumble-dried on permanent press. But this is only because Amanda Waller has her heart. Literally. In a metal suitcase. And Waller controls the otherwise uncontrollable Enchantress by threatening to destroy that heart, which, presumably, would be fatal in a way that having the heart ripped from her chest in the first place was not. Later, when Enchantress gets her heart back, we see her as she truly is: a proto-Cleopatra who, while working her dark magic, twitches and wiggles her hips like an arrhythmic stripper.

David Ayer didn’t write and direct Suicide Squad with comic book fans in mind. He’s worried about the droves of moviegoers who don’t know much about the DC universe and have no idea who these characters are. So he decided to spend what feels like the first half of the movie introducing us to each of our grudging protagonists. Deadshot dotes on his daughter, a twelve-year-old honor student, and wants to become the father he knows she deserves. Harley Quinn was a psychiatrist at Arkham Asylum and fell in love with the Joker (Jared Leto, sporting a fly grill, different-colored contacts, and plenty of greasepaint), her leering, homicidal patient, in what has to be the unlikeliest case of countertransference ever. And so on. And on. The backstories take forever. Harley Quinn’s backstory goes on for so long, and the Joker plays such a prominent part therein, that the audience might reasonably expect him to play an important part in the rest of the movie, too. He doesn’t.

Every minute of the thirty or forty given over to this needless introductory material is one minute less time for the actual story to unfold. The result is a narrative that’s rushed and has no structure. Revelations that come too quickly tend to feel arbitrary. (Wait. Enchantress has a brother who looks like an extra from Stargate? And who’s that sullen Japanese woman with the smoldering katana again?) And arbitrariness in plot development is the death of dramatic tension. When anything goes, nothing really matters. Then the reflective moviegoer is liable to wonder, maybe during one of the prolonged, repetitive, thrill-less, thoroughly interchangeable fight scenes that are used as padding to push the running time past two hours, how a filmmaker with Ayer’s bona fides, the guy who wrote and/or directed such taut, exciting, tightly plotted movies as U-571, Street Kings, and Fury, could suddenly forget how to tell a balanced story.

One possible reason is that there are simply too many characters. That doesn’t mean that there are necessarily too many characters. The Magnificent Seven, for example, manages to use seven protagonists, plus the whiny wannabe, each of them deftly drawn and unique, without turning entropic the way Suicide Squad does. That’s because John Sturges & Co. knew that even with seven heroes, they needed one to provide a center of gravity. And they had Yul Brynner.

Suicide Squad has no center of gravity but would have if Ayer had realized that Will Smith should be the star of the show. Although slightly hard to believe as a hard-bitten assassin, the always-affable Smith manages to wring a few laughs out of the stilted script (unless, as I’m inclined to suspect, he ad-libbed all the funniest lines). And when he’s in the frame, the onscreen chaos seems to abate for a few seconds, just long enough for the viewer to catch his or her breath before the next plunge into swirling piffle. Never underestimate the steadying effect that a genuine star can have on a movie. If Deadshot, with his love for his daughter, and with his portrayer’s charisma and humor, had been the central character here, Suicide Squad might have turned out coherent and entertaining and perhaps even meaningful. Instead, it’s a mess. Such a mess that the audience might not even stop to ask: In a world in which all the heroes seem to be white, why are sixty percent of the villains, not to mention their psychotic handler, various shades of brown?