Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children looks and sounds, especially at first, like a Harry Potter-ish fantasy about growing up (or not) and fitting in (or not), but fundamentally it’s a superhero movie.

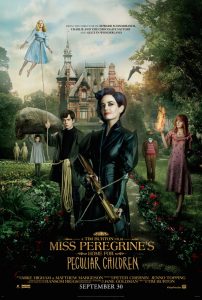

Peculiars are people born with unusual powers (superhuman strength, an ability to make plants grow, invisibility, etc.) and have to hide from a world that doesn’t take kindly to spectacular deviations from the norm. They’re the X-Men, more or less, sans costumes. Protective mentor Miss Peregrine (Eva Green) is Charles Xavier, and Barron (Samuel L. Jackson), the heavy, who’d rather see peculiars take their rightful place as conquerors on the world-historical stage, is Magneto with a sense of humor. The problem with Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children is that the superhero movie hijacks the fantasy movie about halfway through, and the fantasy movie is much subtler and more interesting.

Jake Portman (Asa Butterfield) is our sixteen-year-old hero, and the first thing we learn about him, apart from the fact that he works at a chain drug or department store in Florida, is that he’s paralyzed by shyness around girls. Two minutes in and sexual awakening is a theme. He gets a phone call from his beloved grandfather, Abraham (Terence Stamp, whose face is still one of the most interesting in movies), who believes that he is going to be attacked soon—by whom, and why, he doesn’t say—and he can’t find the key to his gun cabinet. Turns out Jake’s father, Franklin, has the key, because Abe is either psychotic or has dementia, and it wouldn’t be safe for him to have access to a firearm. Jake leaves work to see Abe and make sure he’s taken his medication. When he reaches Abe’s house, he finds his grandfather in the swampy woods out back. Abe’s eyes are missing. He mutters some cryptic last words, clues to a quest that he begs Jake to undertake, and then he dies. This is the mystery that sets the plot in motion. It also presents another theme: the reality of death.

Jake’s parents put their son into therapy, because finding an eyeless body is disturbing and because Jake was extraordinarily close to his grandfather. We get flashbacks of young Jake hanging on Abe’s every word as the old man tells wild tales about his youth during World War II, about fleeing Poland alone after his family was killed, because “there were monsters,” and about the marvelous friends he made at Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children in Wales, where he wound up. Young Jake takes Abe’s stories at face value. Everybody else knows that Abe isn’t all there and that his stories are the crude evasions of a mind tortured by survivor’s guilt. They convince Jake of this painful, mundane truth, and he grows into the disillusioned adolescent we’ve already met. Another theme: the proper place of imagination in the life of a responsible adult.

Jake and his father take a therapeutic trip to Wales. And on the island of Cairnholm, following the clues Abe gave him, Jake finds Miss Peregrine’s house, which is in ruins and has been since the night in September 1943 when a German bomb destroyed it, supposedly killing everyone inside. As it happens, though, Miss Peregrine and her children are very much alive. They exist in a time loop that it’s Miss Peregrine’s special power to create and maintain, living the same day over and over. The loop is what protects them from time and history, i.e., aging and its attendant tragedies, and from the rest of the world, which doesn’t understand them. A fourth theme: the refusal to grow up.

The themes of sex, death, imagination, and growing up are skillfully marshaled and elaborated in the fantasy half of Miss Peregrine’s Home, and if they’re nothing new, they still hold some fascination for those of us with an overdeveloped subjunctivity. The exploration of Miss Peregrine’s world and the introductions to her peculiar children are leisurely and give the viewer a sense of gee-whiz discovery that in some ways enacts the thematic content. Watching the first half of the movie, the viewer is a kind of peculiar, full of childlike wonder at the miracles he or she is witnessing. But then Miss Peregrine’s Home suddenly changes gears. In a flurry of exposition, we’re told about Barron, an evil peculiar who feeds on the eyes of other peculiars, which diet, for reasons unknown, helps him and his followers maintain their precarious outward humanity. We’re also told about Barron’s plan to steal the powers of Ymbrynes, a specific kind of peculiar. Miss Peregrine is an Ymbryne. On cue, Barron appears and kidnaps her. The fantasy movie ends and the superhero movie begins when heretofore beta-male Jake reluctantly embraces his inner hero and leads the peculiar children into battle against Barron and his minions.

The convention of the final showdown isn’t unique to the superhero narrative, but the superhero narrative is uniquely dependent on the convention. Is there a superhero movie that doesn’t culminate in a final showdown? The trouble with this development in Miss Peregrine’s Home is that it completely subsumes everything that came before. All of the fantasy’s thematic richness vanishes in a blur of superheroic action. One of the more affecting situations for Jake in the fantasy portion of the movie is that because of consequential limitations on time travel he may have to choose between seeing his grandfather again and staying with Emma, the lovely peculiar he’s fallen in love with. Part of growing up is learning to accept that you can’t have it all. Jake’s happiness, like everybody else’s, must be touched with loss. A well-worn but poignant idea. But in the either-or triumphalism of the conventional climax, there’s no middle ground, and Jake finds that traveling through time, he doesn’t have to make any difficult choices at all. He can see his grandfather and have Emma. Life’s not so hard after all. It’s just that adults don’t know how to live.

The way Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children shirks its self-imposed responsibilities in favor of a facile happy ending feels like the breaking of a promise, not to mention an aesthetic copout. And this is a shame because Tim Burton was halfway to making a pretty good movie. It’s also a reminder that while Burton likes to deck his creations out in the macabre, he doesn’t really know what the macabre is. For him, the macabre is just a visual style. He dresses like Edward Gorey but thinks like Walt Disney. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but in this case, the Disneyfication of life is much less satisfying than a healthy acceptance of death would have been.