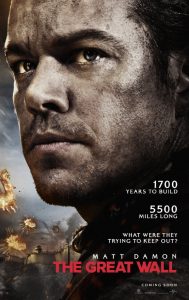

Much has been made about liberal darling Matt Damon’s being cast in the illiberal role of yet another white savior in Yimou Zhang’s The Great Wall. As a matter of fact, the white savior trope is nowhere near the top of the list of what’s wrong with this lousy movie.

At least Mr. Zhang and the bevy of writers on this project, among them the estimable Tony Gilroy, whom I assume was brought in as a script doctor (and found himself being asked to revive a corpse), tried to do something a little different with Matt Damon’s character, William. Usually, the white man has to return to a state of nature in order to find himself and save his soul and does so via descent, or what he thinks is descent, to the supposedly primitive level of whichever natives are handy. Usually, his rebirth has something to do with a sense of belonging, as opposed to the Western way of life, which leads inexorably to isolation and anomie. See under: Avatar and Dances with Wolves. But in The Great Wall, William is a grubby mercenary who’s come to China to steal the natives’ superior technology, specifically gunpowder, which he figures will make him and his fellow swords-for-hire invincible back in Europe. That he turns out to be the toughest hombre in China is predictable and problematic, of course, but hey, he’s basically a caveman compared to the people of the Song dynasty, and what good’s a caveman if he isn’t tough? It’s not like he can give lessons in etiquette or astronomy or scholastic philosophy instead of kicking ass. For what it’s worth, William is not the one who delivers the coup de grace to the monstrous, multitudinous enemy, the Tao Tei. His help is merely indispensable. That may not be much, as subversions of politically dubious convention go, but it’s better than nothing, right?

Compared to the rest of the movie, you could almost count the white savior thing as one of The Great Wall’s strengths. The plot is picture-book simple. William and his Spanish comrade, Tovar (Pedro Pascal), questing, as already mentioned, after gunpowder in China, are captured at the Great Wall and put in shackles. Then the Tao Tei, with impeccable timing, attack. Circumstances being dire, William and Tovar are cut loose and acquit themselves like the seasoned warriors they are. They become honored guests of the wall’s garrison, an army of oath-bound lifers similar to the Night’s Watch in Game of Thrones, here called the Nameless Order. (A Zen koan for you: If you capitalize the N and the O, is it still a nameless order?) Tovar intends to steal some gunpowder at the first opportunity and escape. William, on the other hand, has been looking, unbeknownst even to himself, for a sense of purpose and finds it in the war against the Tao Tei. He decides, after a faux-meaningful lecture from noble, brave, smoking hot Commander Lin (Tian Jing) on trust, to stick around and help defeat China’s terrible enemy. And that’s pretty much it for the story, which will more than meet all of your expectations as long as you expect very little.

With so few procedural complications, the script leaves plenty of room for character development. Alas, neither the writers nor the director are interested in character. The writers seem concerned primarily, if not especially, with teaching us something about Western greed and individualism versus Eastern self-sacrifice and community. And Yimou Zhang only wants to dazzle us with digitized spectacle. In fact, a case could be made that the real protagonists of The Great Wall are the screwy contraptions that the Nameless Order uses to defend the Great Wall. There are enormous catapults that launch enormous, flaming, spiked metal balls; splayed platforms from which Commander Lin and other women in blue armor, armed with spears, bungee jump to within a few feet of the enemy below like suicidal fly fishing lures; giant scissoring blades that emerge directly from the wall; oversized Kongming lanterns unadvisedly repurposed as hot-air balloons; etc. The inventions are so numerous and improbable that you start to wonder whether The Great Wall isn’t a medieval fantasy but pre-modern science fiction, a Middle Kingdom version of steampunk. Maybe we’re witnessing the birth of a new subgenre of SF . . . silkpunk?

Furthering the idea that we’ve wandered into one of science fiction’s remoter precincts is the fact that the Tao Tei are of extraterrestrial origin, or so one gathers from the story that the learned Strategist Wang (Andy Lau) tells about how a meteor landed in the mountains of the north during the reign of an especially greedy and cruel dynasty, and how, subsequently, the Tao Tei swept down from those mountains like a divine punishment, and continue to do so on a regular basis, every sixty years. The Tao Tei are reptilian quadrupeds roughly the size of cows, with crocodilian mouths, clawed feet . . . the usual except for the elaborate ridges of the bony plates on their foreheads, which resemble the face-like taotie motifs found on ritual bronze vessels from dynasties predating the Christian era by many hundreds of years. This adds a subtle touch of authenticity to the Tao Tei but isn’t enough to save them from being boring rip-offs of the Bugs in Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers.

The Great Wall swaggers like an epic. It’s not an epic. Not even close. It’s a cartoon with delusions of grandeur. The seizure-inducing editorial style and overcaffeinated narrative pace seem designed to shorten out attention span because the last thing this movie wants is for us to put more thought into watching it than Yimou Zhang & Co. put into making it. And that wouldn’t take much.